Field Research Around Qaanaaq Coast, Northwestern Greenland 2024

Research teams of the Research Program on Coastal Environments in the fields of marine, glaciers/ice sheet, land/atmosphere, humanities, or others conduct a variety of research observations around Qaanaaq in northwest Greenland from July to September 2024. Please enjoy reports from the research teams along with photos.

Table of Contents

Narwhal sighting survey in Qeqertat, northwest Greenland (2024/9/27)New!

Environmental Acoustics in Qaanaaq, Northwest Greenland (2024/9/26)

Report on the workshop held in Qaanaaq village in northwest Greenland (2024/8/23)

Studying Arctic marine ecosystems through seabirds’ feathers (2024/8/22)

The field campaign at Qaanaaq Glacier, northwestern Greenland (2024/8/2)

Narwhal sighting survey in Qeqertat, northwest Greenland

Writer:Monica Ogawa (Hokkaido University)

Yoko Mitani (Kyoto University)

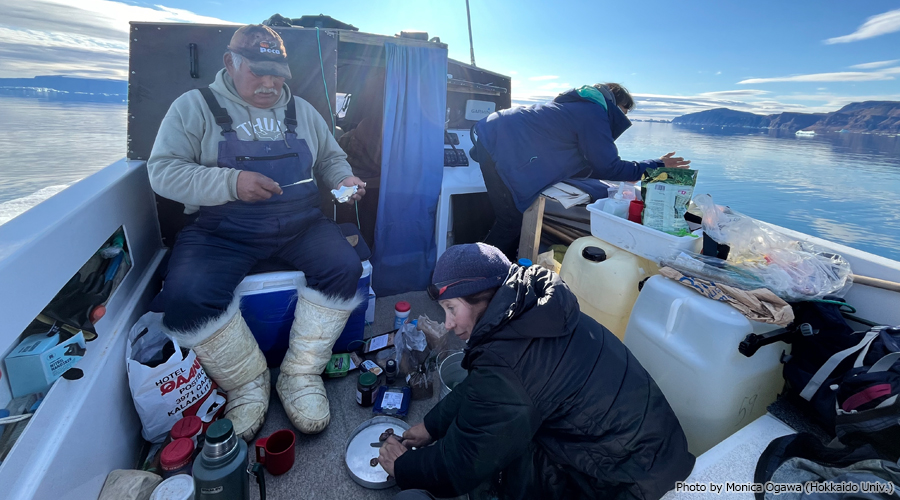

We were once again able to return to Qeqertat to accompany the narwhal hunt!

Qeqertat is the only area where the traditional narwhal hunt using kayaks still remains. Spending several days on a boat with the engine turned off, waiting for the narwhal pods to appear. Then, hunters silently approach them by kayak to hunt.

Narwhals are very skittish, making it impossible to get close with motorboats. However, here in Qeqertat where traditional narwhal hunting is practiced, we can approach them at close range and observe their natural behavior.

We do not return to land until the hunt is successful. This time, we spent seven days floating on the sea with icebergs, surrounded by narwhals, and occasionally seals. The breathtaking views made it impossible to get bored. The Inuit cuisine we enjoy between hunts was always so delicious! My favorite dish is, of course, seal meat – it goes really well with mustard!

This was my second time accompanying the hunt, and my fifth time helping with narwhal processing. I’m gradually beginning to understand Greenlandic, learning the procedures of the hunt, and enjoying interacting with the hunters more and more.

Eventually, we were able to observe over 500 narwhals in total and successfully conducted behavioral observations using a drone. I’m always grateful to the hunters for providing such precious opportunities, and now I’ll begin analyzing the data!

(2024/9/27)

Environmental Acoustics in Qaanaaq, Northwest Greenland

Writer:Evgeny Podolskiy (Hokkaido University)

Tomohiro M. Nakayama (Hokkaido University)

At the end of July and beginning of August 2024, our team completed a mission to retrieve and partially redeploy long-term oceanographic and seismic stations around Inglefield Bredning Fjord in Northwest Greenland. All operations were possible thanks to local pilots skillfully sailing us between icebergs. Our stations were deployed a year ago to the sea floor and on islands near glacier calving fronts for interdisciplinary studies on glaciers, sea ice, ocean, and marine animals.

While retrieving the stations, aerial drone imagery was also taken to generate a Digital Elevation Model of the Bowdoin Glacier calving front. In addition, an NHK TV crew working on a documentary about our research and the region filmed our ocean and land operations from the boat and UAV.

The retrieved oceanographic stations continuously monitored the sounds of the ocean and seawater’s physical properties and performed acoustic profiling of the water column. Seismic stations recorded cryo-seismicity (i.e., ground shaking produced by icebergs and glaciers).

Retrieved data will be analyzed by different specialists. Analysis should reveal (i) the variability in the presence of such acoustic reflectors as zooplankton, fish, and icebergs, (ii) temporal variation of biological, natural, and anthropogenic sounds produced by marine mammals (like narwhals and seals), environment, and humans, and finally, (iii) timing and scale of glacier calving. The data analysis is expected to contribute to a better understanding of ice-clad glacial fjords, which serve as biological hotspots and hunting grounds undergoing rapid environmental changes nowadays.

We also continued observations at Qaanaaq Glacier’s outlet stream between July 19th to August 6th, 2024. In 2023 and earlier years, the bridge over the stream was washed out because of its overflow caused by heavy rain and glacier melting, and the connection between Qaanaaq village and Qaanaaq airport was cut off. To determine the impact of a warmer climate on the village’s society, measurements of the river discharge have been sustained by participants of Japanese expeditions since 2017.

The former method for discharge measurement has been labor and time-consuming. It required an observer to enter the river, measure the depth profile of the stream bed, and repeatedly insert an electromagnetic current meter into the stream, corresponding to a stay in cold water (~2℃) rushing at difficult-to-stand speeds (<2 m/s) for at least 10 minutes.

Motivated by a need to reduce the manual component of observations, this year, we installed four acoustic sensors and three time-lapse cameras near the river for testing and developing a discharge measurement method without entering the river. For this purpose, acoustic sensors were placed between the bridge and the stream’s source (at the Qaanaaq Glacier terminus) approximately every 500 m along the stream length of ~2.5 km. The change of the stream width and geometry might affect the properties of the acoustic signal; thus, we added three time-lapse cameras to capture the dynamics of the stream. Comparison of directly observed discharge with acoustic and imagery data is expected to improve our ability to interpret and employ remote sensing methods for high-frequency monitoring of glacial runoff.

(2024/9/26)

Report on the workshop held in Qaanaaq village in northwest Greenland

Writer:Tatsuya Watanabe (Kitami Institute of Technology)

Tatsuya Fukazawa (Hokkaido University)

We hold workshops every year inviting villagers to learn about research activities in the Qaanaaq region. This year, the workshop was held on July 28, and more villagers than usual gathered at the venue. The number of participants reached a record high of about 70 people, and we could sense that our research activities in this region have taken root, and that the villagers are showing a strong interest in the content and results of our research (Fig. 1).

The workshop began with an opening speech from a local collaborator, Ms. Toku Oshima, followed by Prof. Sugiyama (Institute of Low Temperature Science, Hokkaido University) introducing research themes and researchers of the Coastal Environments team. This year, seven researchers gave presentations, and we were able to provide a wide variety of topics (Fig. 2). In the first half, four presentations were given on the theme of nature. Dr. Podolskiy (Arctic Research Center, Hokkaido University) introduced the biorhythms of appaliarsuk (Alle alle), and underwater acoustics caused by iceberg movement and narwhal behavior, with the theme of the sounds of ice and animals. Ms. Ogawa (PhD student, Hokkaido University) introduced the results of research on marine ecosystems, and the villagers showed great interest in the results of analysis of the stomach contents of seals and narwhals obtained with the cooperation of local hunters. Dr. Thiebot (Hokkaido University) introduced the ecology of seabirds that live around Qaanaaq region, such as appaliarsuk. At the end of the first half, Dr. Nishimura (Shinshu University) of the Cryosphere team, which is also conducting observations based in Qaanaaq village, gave a presentation on their work on snow, ice and meteorology.

During the break time, we prepared sushi, okonomiyaki, and sweets for the villagers to enjoy the taste of Japan (Fig. 3). Everyone’s feedback was very positive, with many saying “Mamartoq! (delicious)”, and the plates were emptied in an instant.

In the second half, three presentations were made with the theme of social impact. Mr. Imazu (PhD student, Hokkaido University) explained the causes of river flooding that occurred in Qaanaaq last summer. Next, the author, Watanabe (Kitami Institute of Technology), gave a presentation on the landslide mechanism in Siorapaluk and slope hazards in the Qaanaaq region. Finally, Dr. Fukazawa (Hokkaido University) gave a talk on village waste issues and the bioconcentration of toxic substances, and presented analysis results showing that contaminated water runoff from the dump site is affecting coastal ecosystems.

After the presentations, there was time for discussion, and we deepened our mutual understanding. Seeing the serious eyes of the participants renewed our determination to accomplish our mission. We will continue to value our relationships with the villagers and engage in research activities aimed at solving the issues and questions facing the community (Fig. 4).

(2024/8/23)

Studying Arctic marine ecosystems through seabirds’ feathers

Writer:Jean-Baptiste Thiebot (Hokkaido University)

Asuka Yushima (Hokkaido University)

Every year, birds renew their feathers to keep a good protection from the weather and an optimal flying ability. The chemical composition of the newly grown feathers will be based on the food that the bird was eating at the time: it is thus possible to study the feeding conditions and the concentration of toxic contaminants that the birds experienced seasonally, just by analyzing their feathers’ composition. And because the feathers from different body areas grow in different seasons, scientists can examine the conditions experienced by the birds in different seasons, by sampling a few feathers from the wing, belly, etc.

Little auks (Alle alle, locally known as “appaliarsuk” in north-western Greenland) are small seabirds (~150 grams) that can be seen almost exclusively in the Arctic, year-round. They can thus be considered good bio-indicators of environmental conditions across seasons in Arctic marine ecosystems. Little auks are extremely abundant, with a large part of their population breeding in northwestern Greenland, where they are seasonally exploited as part of a traditional subsistence harvest by the villagers. In the spring and summer, little auks build a nest under loose rocks in high coastal slopes; they then fly in and out of the nest every day to feed on the marine organisms they can find nearby, and raise their chick. At the end of summer, little auks migrate to the south of Greenland and east of Canada, where they spend the winter eating small crustaceans.

In July-August 2024 we organized a fieldwork trip to a large colony of little auks near the village of Siorapaluk, to sample their feathers. In the two previous years, we were able to study feathers from adult little auks, which provided information on feeding conditions and mercury (Hg) contamination in the late summer and autumn. This time, we were particularly interested in sampling feathers from chicks. First, the down feathers of young chicks reflect the nutritional elements present in the egg while the chick developed: these elements are thus representative of the food that the mother little auks were able to find at sea while growing their eggs, prior to breeding. Second, by sampling the feathers newly grown on chicks before they leave the nest, we will be able to examine the feeding environment that the two parents experienced specifically during the chick-feeding period.

On the last day of our visit, we went on local hunters’ boats, to study the marine distribution of little auks across the fjords. By doing this, we aim to better understand the type of marine conditions that the birds target when searching for food at sea, and to examine the influence of glaciers on these marine conditions.

Biochemical analyses will be conducted this autumn at Hokkaido University to analyze the composition of the feathers, providing new insights on seasonal interactions in Arctic marine ecosystems. In combination with our data collected during the two previous years, these new results will be important to understand how marine ecosystems in the Arctic respond interannually to increasing contamination levels of highly toxic elements such as Mercury, and how this mechanism may affect the people from the Arctic who rely on these marine resources.

(2024/8/22)

The field campaign at Qaanaaq Glacier, northwestern Greenland

Writer:Takuro Imazu (Hokkaido University)

Kotaro Yazawa (Hokkaido University)

Shin Sugiyama (Hokkaido University)

We are in Qaanaaq in northwestern Greenland from July 10 to August 14, 2024 for a field campaign on Qaanaaq Glacier as a part of the ArCS II Research Program on Coastal Environments (Fig. 1). When we arrived at Qaanaaq village, air temperature was 5 degrees, which reminded me winter in Japan. There are many dogs in the village (Fig. 2), sea ice and icebergs in the ocean, and glaciers on the mountains. This is my first trip to Greenland, thus I, Yazawa (Hokkaido University), am impressed at the beautiful landscape.

We have been monitoring mass balance and ice velocity of Qaanaaq Glacier since 2012, by using aluminum poles installed at six locations on the glacier (Fig. 3). The long-term observations are important to understand the evolution of not only Qaanaaq Glacier, but also glaciers and ice caps in northwestern Greenland, where glacier mass loss has accelerated recently. The mass balance observation this summer showed that mean mass loss of Qaanaaq Glacier was 0.52 m w.e. (water equivalent) from 2023 to 2024. The rate of the mass loss was 32% smaller than that in 2022–2023. We also perform ice velocity measurements to investigate the role of ice dynamics in recent mass loss of the glacier. To repeat the mass balance and ice speed measurements next year, we installed new aluminum poles at the survey sites (Fig. 4).

We have repeated UAV surveys since 2022 to study the spatial distribution of surface elevation change with a high spatial and temporal resolutions (Fig. 5). The high resolution aerial photographs are also utilized to investigate supraglacial streams formed by meltwater on the glacier and their influence on the glacier mass loss. This summer, we have performed UAV measurements 3 times, taking 6671 photographs in total. We generate digital elevation models based on the photographs from the UAV. Spatial distribution of surface elevation change and the development of supraglacial streams are investigated by comparing the results with those from 2022 and 2023.

(2024/8/2)